The Future: the Robots are Japanese, the Japanese are Robots, and the Pigs Want to be Eaten

Don't look now but a thing associated with "punk" is reactionary

I had the bad luck of revisiting the short work of Philip K. Dick at just about the time that the monocultural discourse (such as it is) saw one of its periodic reentries of science fiction — what it is, what it does, what it means — in classic Kool-Aid Man fashion. I speak here of Cyberpunk 2077, a video game blockbuster of that preordained kind that used to be endemic to summer movieplexes. I don’t really want to talk about the game itself so much, though its relationship to cinema is probably worth excoriating in detail. But cyberpunk, small c? I can write around it, if not about it.

Like any genre, especially one that’s attracted significant monetary investments, cyberpunk is a contested concept. In my layman’s mind I see a series of layers to it, each with its degree of ornamental importance decreasing inversely to its spiritual importance. These facets are: Aesthetics, transhumanist perspective, and internal alienation. The further down the list you go, the less importance audiences generally ascribe to the particular element, I think. But in terms of what makes it interesting, it’s an ascending sequence.

I would place cyberpunk’s vaunted relationship with 1980s economics into the first category. Just about every nerd will tell you that the dominant aesthetic mode of cyberpunk originates with the art design of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner and the prose fiction of William Gibson’s Neuromancer. Whatever their origins, you can probably visualize all the touchstones — filthy, fog-ridden streets, neon signage, hyper-modernist metal-and-black-glass architecture, metal-and-LED prosthetics. And, most importantly, kanji script.

The prominence of Japan and sinophobia generally in classicist cyberpunk is something that’s been well-documented, and it’s something that seriously complicates (I would say, neutralizes) just about any class-conscious analysis of the fiction. The nutshell summary: Far-eastern imagery in 1980’s cyberpunk derived from the perspective of a western culture of working class manufacturing, in rapid decline under the outsourcing of labor markets, while tech-forward “Eastern Tigers” seemed on unstoppable ascent.

Insofar as the present informs science fiction futures, Blade Runner envisions, from a feverish western perspective, Japan’s soft conquest of the Earth. The omnipresence of kanji is not (just) exoticism, but a kind of sociocultural masochist roleplay, in which the west imagines what it’s like when English is not the trade language / lingua franca across the world.

There’s more to it than just the macro perspective, though. At first blush, the hyper-commercial, stratified societies of cyberpunk might seem pretty straightforward in terms of what they say about class and culture. It can appear to constitute a kind of generic, natural anti-corporate reaction just as easily derived from the domestic austerities of Reagan and Thatcher as from the arrival of globalized foreign industry in English-speaking countries.

But I think the fact of receding civic government in the face of corporate government — universal as it is to centrist and right-wing politics the world over — matters less than the kind of corporate government that’s depicted.

To wit, European (and to some lesser extent, American) sensibilities around work have typically placed management and labor in adversarial negotiation. Unionizing, etc. But when you read studies of business in the 1980’s, you start to perceive a contrasting narrative around the far east. Scholars and pundits of the time sought some explanation of why eastern economies were so strong when the deregulatory environment of the west was not.

Conservative economists (which is to say, most all economists) were highly reticent to stick with the simplest explanation for the state of the markets: That eastern governments had pursued pretty strict protectionist trade policies and “sponsored” tech-forward industries such that when western countries dropped their own protectionist policies, western industry simply couldn’t compete. Such a narrative insinuated that laissez-faire economics championed by the right wing didn’t make a strong economy so much as a rich investment sector. Needless to say, it was an inadequate explanation.

One of the counter-narratives that emerged and became favored revolved around a putatively “eastern” way of managing business. Generally this came to be called TQM: “Total Quality Management”. While western companies since Ford’s first assembly line had typically aligned behind "scientific management” — the gauging of achievement via simple calculus, the kind of “scans per minute” metrics that have endured through to the present in blue-collar work of all kinds — eastern companies took a different approach.

If you work in the present day, most of TQM’s features are things that you are more than likely familiar with, especially in tech and white collar work: small teams that “own” their portion of producing whatever product or service, and regularly analyze how their work can be streamlined or made clearer (among other things, TQM is the notable precursor to MBA seminar-cults such as Lean and Six Sigma).

From an analytic standpoint, this approach just meant better quality control generally; businesses with more “holistic awareness” of how they operated were better equipped to identify defects not just in production, but in product design, and fix them at less cost and time commitment. But it’s easy to forget, in retrospect, how much these things were taken for granted in western business.

Of course, the language barrier and even the faintest whiff of communalism, the notion that even managers subsume their ego to the whims of the firm (another new concept endemic to TQM: “Company culture”) were enough to skew the popular depiction of this difference in profoundly racist ways. A lot of recent-vintage stereotypes of the Japanese really came to the fore, in a big way. Michael Crichton had a whole corporate espionage book that isn’t cyberpunk but sort of feels that way, on account of how scary the entire concept of Japan is meant to be. And this is all taking place in a liberalized, capitalist global economy! There wasn’t even a Cultural Revolution to name and claim actual dissolution of the individual into the collective.

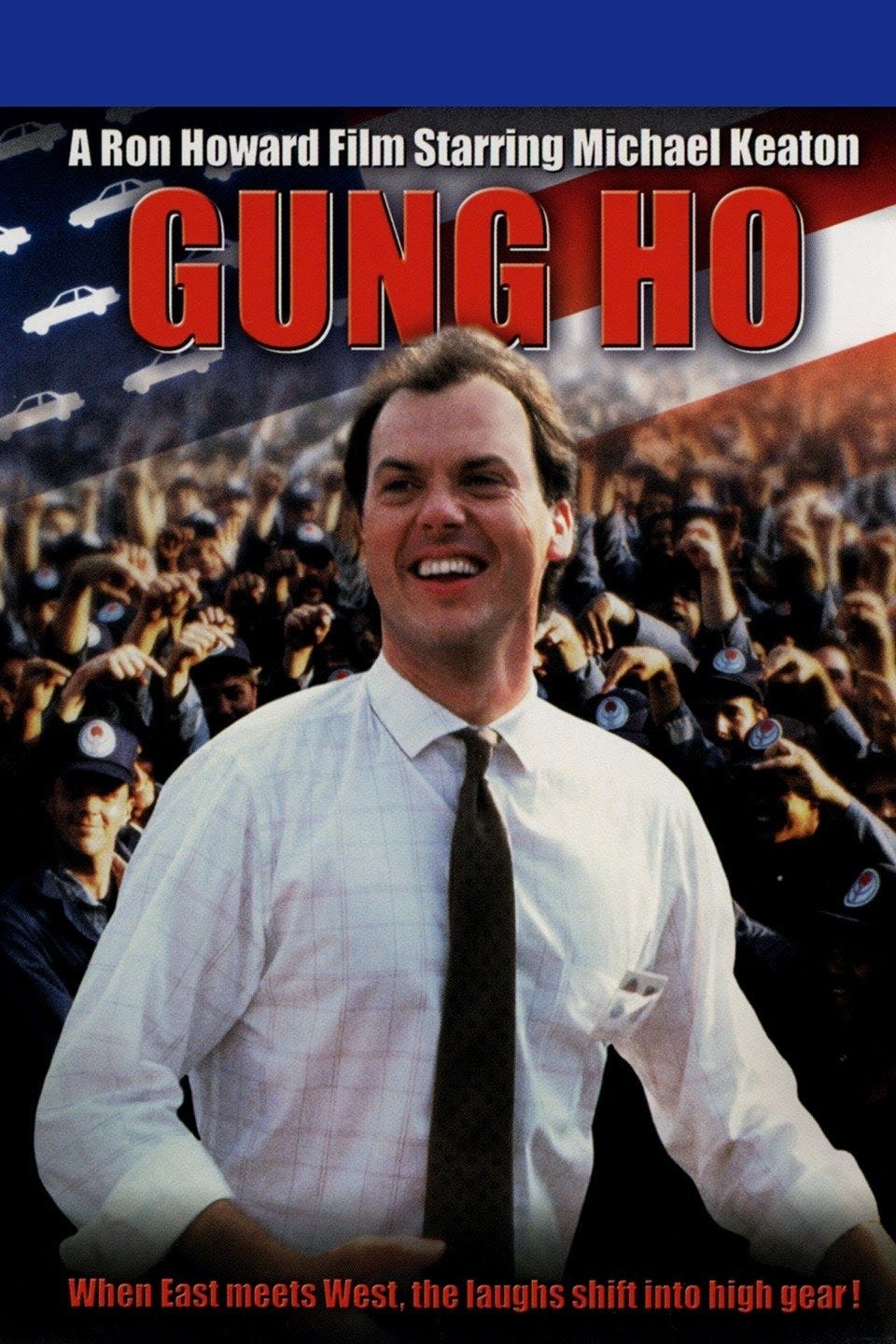

Take Gung Ho, probably the prototypical “culture clash” “comedy” of this type, boiling all this heinousness down to the Trading Places mean: Blue collar American workingmen have to live and learn when the Japanese take over their auto plant! They’re strange! They do morning exercises together! By the end everyone’s a little bit more human, and I’m a little bit closer to death. And to tie it all into a bow, as Wikipedia helpfully states:

The title is an Americanized Chinese expression, for "work" and "together"

Thus the modern Japanese (Korean, Indonesian, Singaporean, whatever) person becomes the platonic drone, dutiful and efficient and so sexless and maximally repressed that, in a weird horseshoe theory sort of way, they become maximally perverted (I think these assumptions say way more about WASPs, tbh) And it’s a flavor that blends naturally with yellow peril notions of deeper vintage. Whatever the case, they’re just not like us.

So, cyberpunk! This kind of “culture clash” is definitional to the future shock of the aesthetic. The mega-corporations that run everything in Blade Runner and Cyberpunk 2077 are very much derived from a specifically sinophobic variant of the faceless Eastern menace. This puts them on a different track from the fascination-repulsion of corporate power evinced in, say, Oliver Stone’s Wall Street, even as they’re populated, as big money businesses are in life, with grasping psychopaths.

The thing that continually fascinates me about systems theory in any permutation is the contention (rather indisputable, imo) that social systems exist both within and without their membership. That is to say: A collective entity can be comprised of people, people who benefit from or are victim to its inputs and outputs, and at the same time exist outside of them. That is to say that an entity like a nation, or a corporate business, is something between an engine and the Ship of Theseus. They are beyond conspiracy. They consume and project power not for the purpose of benefiting John Galt executives but because they have charters, machine codes, exogenous wills and orphaned desires that seem to come from nowhere specific but are enforced with the power of a God.

At its barest and ugliest, depictions of hyper-capitalism and consumerism in genre like cyberpunk gun for this specific and depressing insight — not for nothing that cyberpunk is indelibly paired and blended with noir, another genre of destructive social structures that found resurgence in the pitiless 1980s — but when it swings, as it so often does, into sinophobic aesthetics, the racist past is put to task in service of the point, and the point is lost.

The Arasaka Corporation of Cyberpunk 2077 is almost literally chthonic in its boundless presence and reach, its unchecked power over life and death — and its namesake executive is, literally, a 150-year old sinofascist kamikaze pilot, its psychotic cyborg assassin-agents consumed with depersonalizing facsimiles of honor and bushido. Japan and its culture becomes synonymous with selfless bureaucracy in the service of death. It’s not a good look.

I mentioned Philip K. Dick up top because he is the godfather of cyberpunk — and he did, famously, sign off on Blade Runner as an essentially precise replication (lol) of his mind’s eye — and I was going to go into a whole thing about how the genre’s development into being “about” technology was rather beside his preoccupations. I think the porousness of self that defined Dick’s extraordinary vision went far beyond constructivist theory-of-mind problems and AI paranoia. I was also going to spend some time denigrating transhumanism, or maybe just cyberpunk’s (and Cyberpunk’s) failures of it. But this has gotten overlong as-is. Just let it be known that it is, almost inevitably, aesthetic before art. Or in other words, pulp.